Vulnerability: The Bridge Between Horizontal and Vertical Trust

Trust comes in two forms—across the team and up and down the chain of authority. Both depend on leaders and teammates willing to show vulnerability.

Trust is the lifeblood of any organization. Without it, no amount of talent or resources will prevent dysfunction. What we often overlook, though, is that trust comes in two forms. Horizontal trust—the bonds among peers and teammates—and vertical trust—the confidence between leaders and those they lead. Both are essential. And both are rooted in vulnerability.

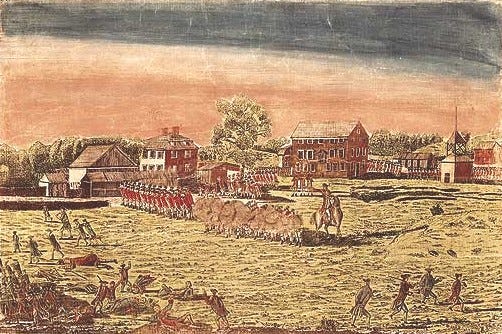

Horizontal trust grows when people are willing to show their humanity to one another. That means sharing doubts, offering help, and admitting mistakes. One of the venues that we at R. Lynch Enterprises use for our leadership tours is in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, studying leaders’ actions there in the early stages of our Revolutionary War. One thing about the militias at Lexington and Concord, and with militias all over Massachusetts at the time, was that neighbors trusted each other and their elected leaders. This wasn’t because they wore uniforms or were given rank; rather, it was because they were honest about their fears, their inadequacies in confronting the well-drilled British regulars, and their willingness to stand together, shoulder to shoulder, inspired by their steadfast belief in nascent American values. In today’s organizations, this is the kind of trust that develops when colleagues know they can lean on one another without judgment. Vulnerability—saying “I don’t know” or “I need help”—makes that possible.

Vertical trust, by contrast, is built when leaders show that they are steady, competent, and accountable. But it also demands vulnerability. Leaders who pretend to have all the answers and seek little to no input eventually lose credibility. As I wrote in Large and In Charge No More—A Journey to Vulnerable Leadership, “When leaders drop the armor of certainty, they invite others into the problem-solving process and strengthen, rather than weaken, authority.” People don’t expect perfection from leaders; they expect honesty and the humility to admit and own mistakes. That is where vertical trust flourishes.

The interplay of these two forms of trust is powerful. Without horizontal trust, teams fracture into disconnected silos. Without vertical trust, organizations drift without direction. Vulnerability is the bridge that connects both: it gives peers permission to be real with each other, and it allows leaders to be authentic without forfeiting respect. When both forms of trust are present, organizations can weather uncertainty, conflict, and change.

Today, we often prize bravado, decisiveness, or image over vulnerability. But Lexington and Concord remind us of another truth: trust—whether across the ranks or up and down the chain—emerges when people are willing to show their humanity. Leaders today who want to build resilient organizations would do well to remember this. Vulnerability is not weakness; it is the source of the strongest bonds we can form.

Love this--especially the connection to Lexington and Concord.

Question for you, during your service in the Army, did you ever see instances whereby a leader was forced to deal with an unruly subordinate? I'm talking specifically about those subordinates that have big egos and often clash with their superiors. I've been studying this concept and would love to get your feedback.

From what you've written, it seems that leveraging both vertical and horizontal trust would be useful in tolerating these hard-to-work-with type individuals.